White-tail spiders have re-entered the news time and time again, accompanied with gory photos of open wounds, necrosis (death of tissues of the body), and heavily ulcerated skin.

Headlines like “White-tail spider bite puts Palmerston North man in hospital, left unable to walk”, “Tourist loses both legs — and arms at risk — after ‘possible white-tailed spider bite” and “Sydney mum loses leg after white-tailed spider bite” don’t paint a nice picture of this seemingly monstrous critter.

However, with further reading of these and countless other articles, you will quickly realise that there is no definitive proof that white-tail spiders are the culprit, but rather highlighted with a level of undeserved infamy.

What is a white-tail spider?

White-tail spiders are a group of spiders with nearly 200 species in Australia, and only a handful of other species living elsewhere. The two most common species: Lampona cylindrata and Lampona murina, are the usual suspects highlighted in media as they are more common to find in households compared to their other eight-legged comrades. These spiders mostly consume other spiders, playing a very important role by controlling populations of indoor pests, including common black house spiders, daddy long legs and redback spiders.

In some respect, white tail spiders could be the best housemate you have (knowingly or unknowingly) ever had. Rather than build webs, these spiders wander at night in search of food and will actively avoid confrontation with humans. Research investigating 130 white-tail spider bites showed that in all cases, spiders were accidentally encountered between sheets, towels or clothing.

What does a white-tail spider look like?

White-tail spiders are generally medium in size, varying from 3 – 13mm for different species. Their name (not leaving much up to imagination) is indicative of the white “tail” or mark on the surface of their lower abdomen. Their body is darkly coloured and distinctly described as cigar-shaped, with slender legs often exhibiting lighter coloured banding.

Are white-tail spiders dangerous?

It’s easy to assume that white-tail spiders are extremely dangerous. We’re taught from a young age that fearing spiders should be intrinsic, whereas loving and appreciating them needs to be a learnt skill – a skill seemingly reserved for arachnologists. This intrinsic fear, in tandem with the media vilifying spiders would lead us to think that yes, these spiders are a threat to humans. However, this is not the case at all and the sheer lack of strong evidence linking skin necrosis and white-tail spiders is alarming.

Out of 130 confirmed white-tail spider bites, researchers found not a single case of necrosis, with no longer than 24-hours’ worth of localised discomfort, redness, and/or itchiness.

Data has shown that necrosis caused by a spider bite is extremely unlikely, with most cases of spider-induced necrosis being a cause of misattribution. Cases such as skin cancer, bacterial or fungal infections, golden staph and even feigned spider bites have all been attributed to white tails.

It’s easy to assume that the sudden pain in your leg can be attributed to a white-tail spider bite. After all, you saw one in your linen cupboard just a few days ago! After doing some frantic googling and reading headlines like “Australia’s most dangerous spider bite” or “spider-induced necrosis” you visit a doctor who, without doing any tests, incorrectly diagnoses you as a white-tail spider bite victim. After worsening symptoms, you realise that your “spider bite” hasn’t actually been caused by a spider at all, and is more likely to be an unrelated and undiagnosed skin infection.

In my humble opinion (and that of other professionals), the misattribution of white-tail spider bites is potentially more dangerous than the spider itself.

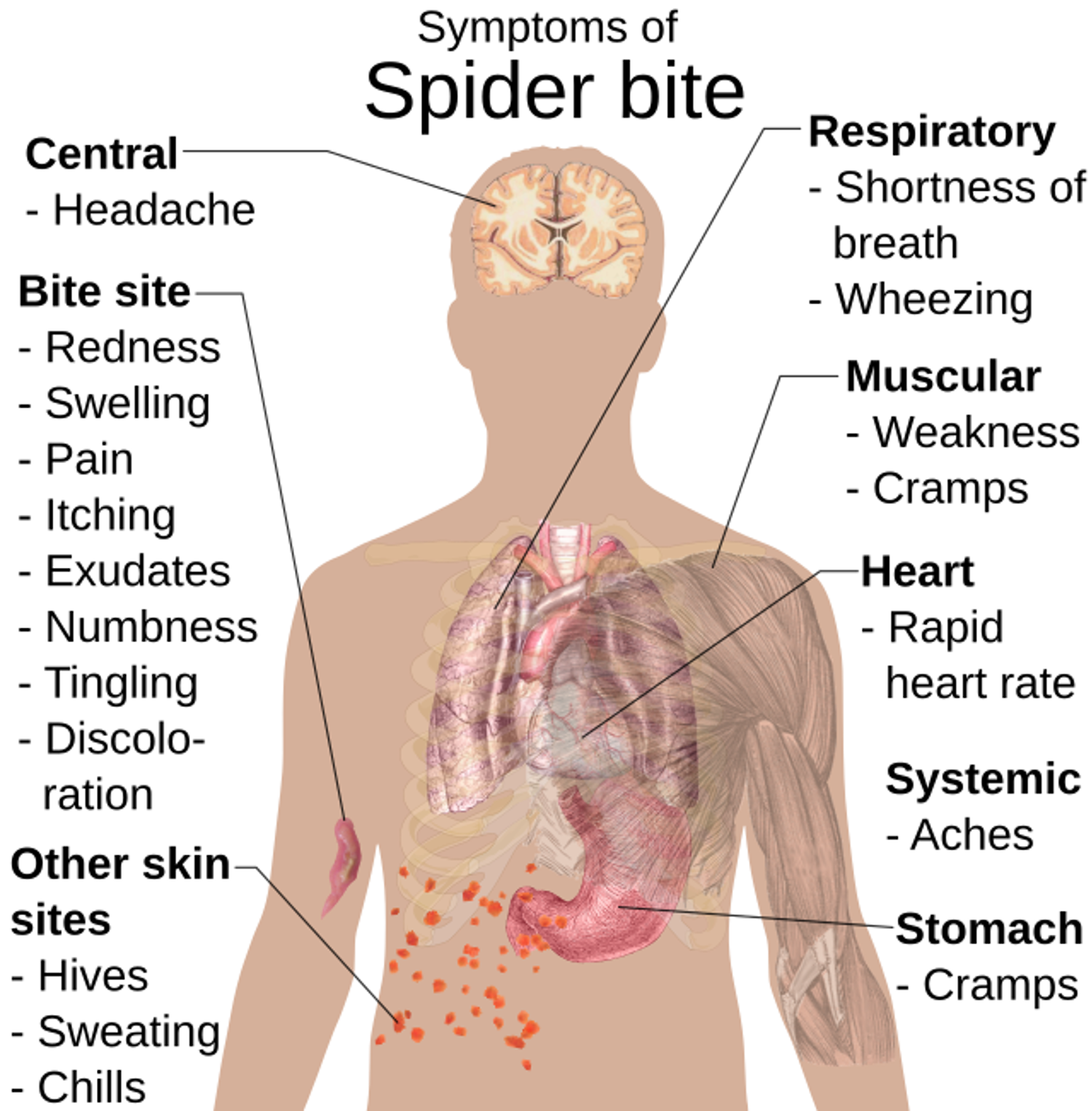

This is not to say that these spiders aren’t dangerous; their bites can cause mild pain and discomfort, yet this rarely exceeds 24 hours. In some severe cases, nausea and headaches can develop, with certain people having a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) to the bite.

What does a white-tail spider bite look like?

If you are bitten by a white-tail spider, visible puncture marks will be evident on the skin with localised redness and swelling. Generally, mild pain and discomfort can be expected with potential itching and/or burning at the bite site. These symptoms are only temporary and should disappear within 24 hours after the bite.

In very rare but more severe cases, some people can experience severe pain and discomfort as well as nausea, headaches, and vomiting. If symptoms of anaphylaxis occur, urgent medical attention is required.

How do you treat a white-tail spider bite?

Often, only temporary treatment is required with no need for aid by a medical professional due to the mildness of the venom. Treatment includes holding a cold press on the affected area for periods of (no more than) 20 minutes and monitoring your symptoms. If symptoms persist or you are experiencing severe pain, nausea, headaches and/or vomiting, seek out a medical professional.

While the white-tail spider is often portrayed as a dangerous threat responsible for gruesome open wounds, necrosis and limb amputation, the evidence does not support this reputation. The alarming headlines and gory images associated with this spider have contributed to its infamy, yet definitive proof of its culpability is lacking. Instead, the white-tail spider appears to be a misunderstood arachnid, unjustly blamed for severe medical conditions that may have other causes. By examining the facts, it becomes clear that the fear surrounding the white-tail spider is largely based on misinformation and sensationalism.

Research at UniSC

UniSC researchers are powerful innovators, bringing ground breaking knowledge to complex issues facing our regions and our world.

Charlotte Raven, PhD candidate investigating the impacts of disturbance on rain forest function, recovery and invertebrate communities, University of the Sunshine Coast

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au